By Mirah Riben

In a public hearing before the Assembly Institutions, Health and Welfare Committee on Adoption, December 9, 1981, in Trenton, New Jersey, attorney Harold Cassidy made the following impassioned plea:

There is a need for us in society to learn to know the women who have come to call themselves ‘birth-mothers.’ They are women who know that a child is part of his mother forever… They know the pain of wanting what is best for the child they love, while society tells them that what is best is that they never see that child again… They know the neverending grief of being continually denied what every portion of their souls demands: the knowledge that their children are well.

We, as a society, have perpetrated the crudest deception. What we have believed to be altruistic has been, in reality, destructive. We have sought to create without any understanding of how much we destroy in the process.

Birth parents now know that separating a mother and her child is not in the best interests of either of them. Their enormous sacrifice was based on society’s misconceptions. The adoptees’ sense of rejection is the most painful irony of all: What was done out of love is mistaken for a lack of it.

For us to truly learn what a birthparent is, is to learn that we, as a society, are hypocritical. We urge surrender, then later rebuke it. We make laws that we purport to be for the welfare of our children, then ignore or suppress their pleas to satisfy the most fundamental and compelling need they have: to know their mothers.

What we must understand is that we have held imprisoned an important part of these women. They must be made whole again. This task will not be difficult when we understand who they are.

They are our mothers. They are our sisters. They are our daughters.

Ann Fessler first raised awareness of and brought understanding to this population in her 2007 book, The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade.

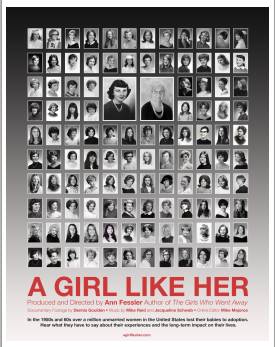

Fessler has done it again in a moving documentary, A Girl Like Her. (Distributed by Women Make Movies, NY). The 45-minute feature film depicts young women caught in the quagmire of puritanical mores of the ‘50s and ‘60s while trying to be cool, popular (and loved) teenagers. It adds to the library of films, such as Philomena, which poignantly show adoption from the perspective of the mothers for whom it is a loss.

From 2002 to 2005, Fessler interviewed a hundred women from all over the continental United States. They ranged in age from 48 to 84 at the time of their interviews, having birthed their children when they were 15 to 35 years of age.

Black-and-white film clips turn back the clock, giving us a view of the post-WWII era. Over this backdrop, Fessler restores the voices of these silenced women. We hear from women who were labelled “wayward girls,” “loose” and “unwed mothers” in an era before single parenthood was accepted.

The women share the discovery of their pregnancies, how their parents reacted, how they felt like disappointments and their total lack of say in deciding how the “problem” was to be handled. Given no option other than relinquishing their children, they were berated, disgraced and humiliated; their will was broken. Cast out by their families, the “black sheep” were herded to Homes for Unwed Mothers, weighed down with a heavy mantle of shame. What the women describe is methodical emotional abuse that leaves deep scars.

The 1950s and ‘60s were said to be an “innocent” time. Kids played outside, and sex was never mentioned. Prime-time television shows like Father Knows Best andLeave it to Beaver depicted married couples sleeping in separate beds. Girls whispered about how babies were made. Boys told us we couldn’t get pregnant the first time we had sex or if we hadn’t begun menstruating yet.

Gender roles were impenetrable. Girls were expected to be “good girls,” quiet and obedient. They were programmed and conditioned to grow into subservient and submissive wives by attending mandatory homemaking, sewing and cooking classes while boys took shop and automotive classes. It was the girls’ “job” to find a “good catch”, and they were subjected to conflicting messages such as being told to “let boys win.”

From time to time girls in schools throughout the nation disappeared for the better part of a year to stay with an aunt out of state. The rumor mill, however, said she “gotten in trouble”…”gotten herself pregnant.” Fessler takes us inside the world of these disappeared girls.

The Legacy of Trauma

Nearly one-third — 30 — of the one hundred women Fessler interviewed had no subsequent children. The reasons, she told me, varied. The following are non-scientific observations of Ann Fessler about the women she interviewed. A compilation of actual studies of this population are available here:

• They didn’t feel worthy. Some said it was drummed into them over and over that they could not be a good mother — that they were bad and not mother material; unfit.

• They felt it would be disrespectful to, or would dishonor, the child they didn’t raise. These women hoped they they might meet their child one day, and how would they explain that they could raise other children but not the child they surrendered? This was often combined with a sense of not being worthy.

• The birth and surrender was traumatic for them, and they didn’t feel they could go through it again. All of their associations with birth were negative. One woman is unable to tolerate hearing babies cry. Another said she just couldn’t be around babies; it was too painful.

• Some felt worthless and like “damaged goods” after the ordeal and formed relationships with men who were not “father material” — perhaps intentionally, or perhaps just because they didn’t think they deserved a “good guy” and… “What if he finds out?”

• Several women chose sterilization. At least three, and maybe as many as five of the hundred chose this route. They were single; birth control pills were difficult to obtain; and they were petrified of getting pregnant again (outside of marriage).

• Some women tried for a long, long time to get pregnant and couldn’t. They experienced something called secondary infertility. Three of the women later adopted children: two via the foster care system (where the children had contact with their parents and other siblings) and one adopted internationally.

Secondary infertility, intentional or otherwise, is not the only long-lasting effect that belies the assurances of parents, social workers and clergy that the mothers would “forget” the trauma of surrendering their children. Since 1978, researchers found that mothers who relinquished children to adoption suffer continued loss, pain, and mourning that does not diminish over time, but increases. The grief and was called “severe and disabling” by some researchers.

As many as 80 percent of the women Fessler interviewed have been reunited with their adopted-out children. While many thought it should be their child’s choice, and others had no idea how to search, none feared being found. Even those who had family members who had no idea that they had had a child that had been surrendered, they reported that they would be delighted to figure how to tell them if they were contacted.

To What End?

The film is not only important to all individuals and families whose lives are affected by adoption — it also offers an opportunity for the rest of us to learn from this time in history and to stop repeating past mistakes.

Disgrace for being pregnant outside of marriage is no longer an American issue, yet we lack social supports such as affordable day care to level the playing field, allowing less-than-affluent women and their children to remain together.

Demand for children to adopt, however, remains high. Women are waiting longer to start families, resulting in high infertility rates, and gay marriage adds to the competition. As a result, one nation after another is “mined” for babies to fill the demand. Mothers from Central America, Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa hurt no less when their children are lost to adoption — often being stolen and trafficked, or taken with the use of deception.

These mothers deserve our understanding, and more importantly, they deserve not to be exploited by child traffickers and baby brokers for their sought-after children.

Read at the Source: :

How can adoptive parents as human beings not understand the anguish of birth mothers? Adoptive parents stole children from birth mothers by their complicity .How I wished when I was pregnant that adoption did not exist so I could take care of my child. myself but competing with couples from middle-class background I was denounced as being selfish depriving my child of parents to educate him. The sacred bond between mother child was ignored and child was taken and birth mother was denounced as worthless person. Adoptive parents are in denial but must one day admit to the fact ie I stole a child from a vulnerable weak riefstriken mother